Physicists have long wondered about a unifying theory that amalgamates the fundamental reality of the universe. Their tremendous intellect is enviable, unfortunately, not their assigned undertaking. Thankfully, for us lesser beings, the quest for a unifying theory of investing is made infinitely painless:-

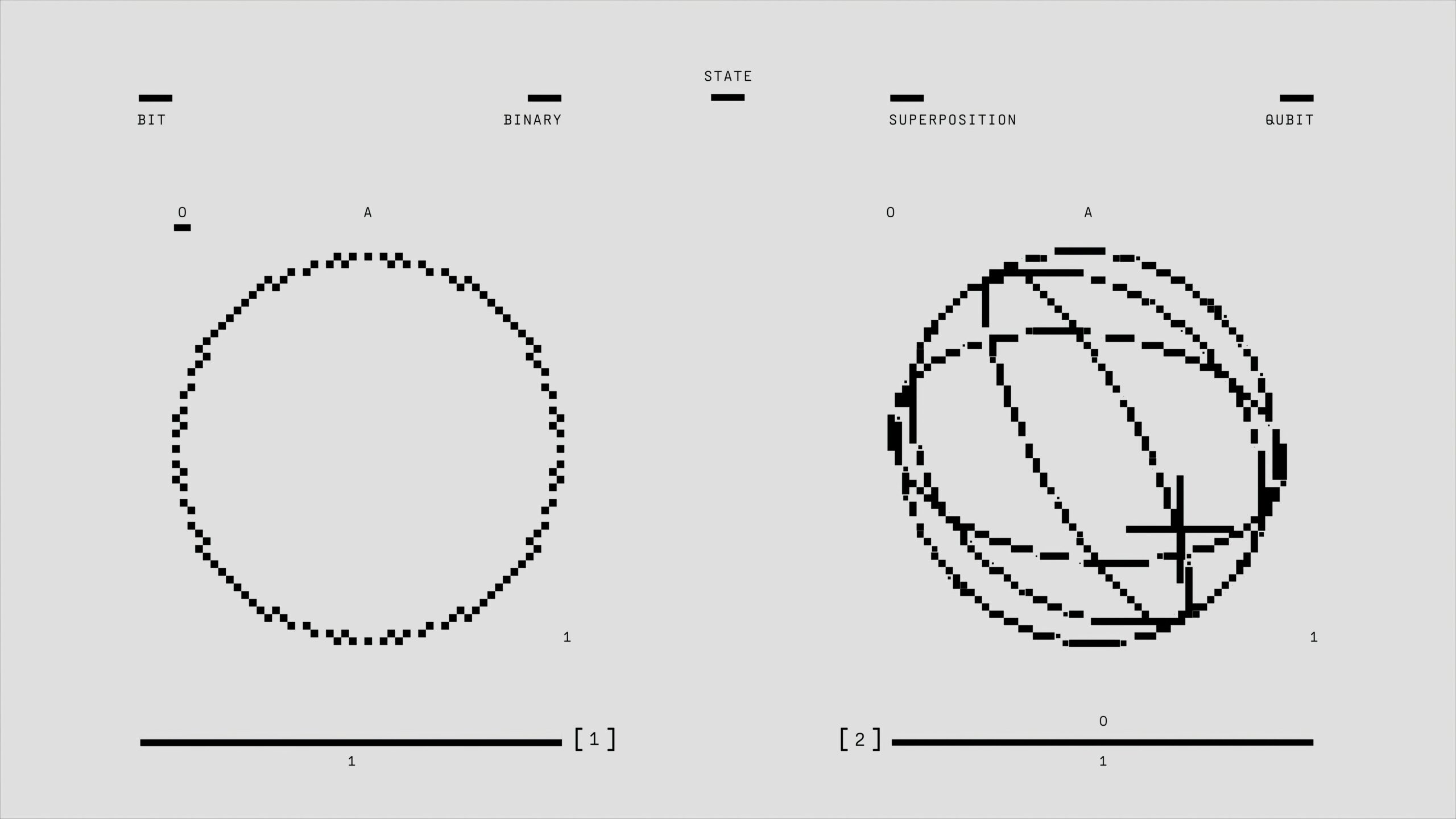

Investing = Price/Value.

This seems straightforward enough. Notwithstanding, multiple layers remain before heaving a sigh of confident relief and going about debuting as a fund manager. Simple as it sounds, there is more than what meets the eye.

Let’s start by unpacking the numerator, price. This represents nothing more than the number quoted by Mr. Market. As the famed chapter eight of The Intelligent Investor dictates, long heralded as the best chapter by Warren Buffett, price is what you pay for.

In other words, price is but the figure that balances both supply and demand for a particular investment in the market, the net balance of all willing buyers and sellers. In private markets, the mechanism remains similar, except with more bargaining and fewer participants.

But what about the denominator, Value? A keen observer might point out the similarity between the famed P/E ratio and the aforementioned Price/Value. This begs the question: why bother with this Price to Value formulation at all?

The short answer is that earnings are just one proxy for value, but not a measure of value itself. When investors use metrics such as P/E, P/B, ROE, or profit margins, they are using quantitative approximations to triangulate something that is ultimately qualitative in nature. That is, a business’s intrinsic ability to generate future cash flows.

One could build a case for the statement of cash flow being the accounting proxy for this fundamental economic reality, but in truth, value is a function of a blend of qualities. Competitive positioning, industry dynamics, capital intensity, customer stickiness, cost structure, management capability, and risk— all of which collectively shape the long-term value and durability of a business.

To some extent, the earnings figure captures this essence, functioning as the “filtrate” after considering all the “filters” that convert the top line into the supposedly be-all-and-end-all bottom line.

If you will, the filters act as a checklist of factors rendered by auditors and regulators. Although reality is often messy, one might argue that a base threshold has been set. At the very least, checks and balances have been enacted (though the enforcement of regulations is a different story) to provide a measure of numerical accountability.

Accounting 101 instructs that revenue translates into gross profit after accounting for direct costs. Upon considering operating efficiency, this then trickles down the income statement as operating profit, and finally into net income, given the tax and interest burden borne.

As a result, net income has been fashioned as the most telling figure companies display, as it reflects the net outcome of the company’s growth thus far, current operating efficiencies, and financial leverage. Nonetheless, it is paramount to highlight that this follows from the company’s competitive moat, not least its position within the industry and the capital intensity on which the business runs. Financial statements are a numerical yet imperfect account of these factors.

This can’t be stressed enough.

Customer-supplier relationships, technological know-how, and marketing savvy are but a few of the many qualitative factors to consider; the commercial implications of which include greater profit margins & revenue growth, larger R&D expenses & patents held (or rather, the allocation of the R&D budget as R&D isn’t always commercializable), and a higher asset turnover figure. Interestingly enough, most of these factors can be subsumed under managerial capability and risk. But that’s a topic for another time.

For this reason, earnings can only approximate, but do not equate, value, emphasizing the need for qualitative tools to solidify one’s confidence in the earnings figure. As such, the estimation of future cash flows is neither art nor science but both, with the scientific aspect being the manifestation of the artist’s sleight.

The only problem? Most analysts know of this already. Yet, funnily enough, industry veterans still chase the earnings figure like a pot of gold. More often than not, stock prices trend upwards upon positive earnings announcements.

Reiterating Warren Buffett, price is what you pay, value is what you get. A company’s future cash earnings are ultimately what drive value; unfortunately, this has been blurred by accounting rules and managerial distortions, not to mention the startup world of storyboarding.

Although it appears the prospects for widespread use of Buffet’s look-through earnings seem remote, a hopeful reminder is that overlooked places often belie investment opportunities.

Leave a Reply